Monte Carlo Simulations in R

If there is one trick you should know about probability, its how to write a Monte Carlo simulation. If you can program, even just a little, you can write a Monte Carlo simulation. Most of my work is in either R or Python, these examples will all be in R since out-of-the-box R has more tools to run simulations. The basics of a Monte Carlo simulation are simply to model your problem, and than randomly simulate it until you get an answer. The best way to explain is to just run through a bunch of examples, so let's go!

Integration

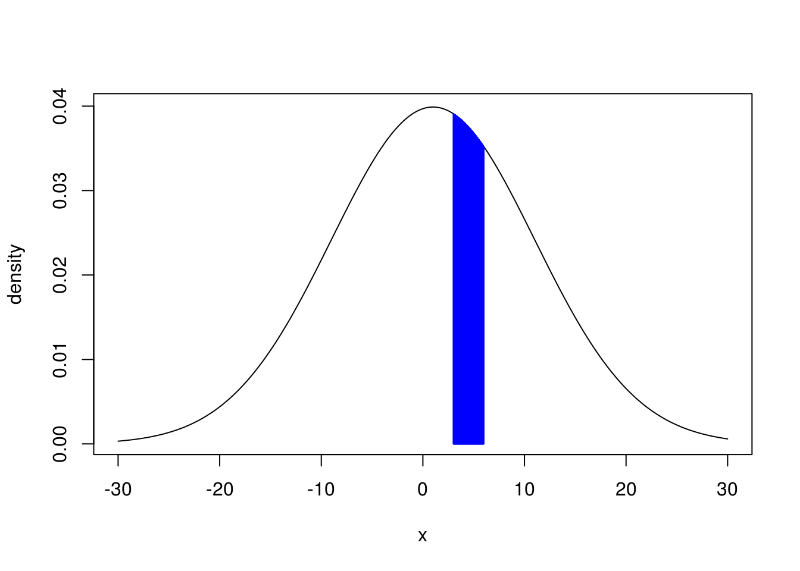

We'll start with basic integration. Suppose we have an instance of a Normal distribution with a mean of 1 and a standard deviation of 10. Then we want to find the integral from 3 to 6 \(\int_{x=3}^6 \mathcal{N}(x;1,10) \) as visualized below

In blue is the area we wish to integrate over

We can simply write a simulation that samples from this distribution 100,000 times and see how many values are between 3 and 6.

runs <- 100000 sims <- rnorm(runs,mean=1,sd=10) mc.integral <- sum(sims >= 3 & sims <= 6)/runs

The result we get is:

mc.integral = 0.1122

Which isn't too far off from the 0.112203 that Wolfram Alpha gives us. If you’re interested in learning more Monte Carlo integration check out the post on Why Bayesian Statistics needs Monte-Carlo methods.

Approximating the Binomial Distribution

We flip a coin 10 times and we want to know the probability of getting more than 3 heads. Now this is a trivial problem for the Binomial distribution, but suppose we have forgotten about this or never learned it in the first place. We can easily solve this problem with a Monte Carlo Simulation. We'll use the common trick of representing tails with 0 and heads with 1, then simulate 10 coin tosses 100,000 times and see how often that happens.

runs <- 100000 #one.trail simulates a single round of toss 10 coins #and returns true if the number of heads is > 3 one.trial <- function(){ sum(sample(c(0,1),10,replace=T)) > 3 } #now we repeat that trial 'runs' times. mc.binom <- sum(replicate(runs,one.trial()))/runs

For our ad hoc Binomial distribution we get

mc.binom = 0.8279

Which we can compare to R's builtin Binomial distribution function

pbinom(3,10,0.5,lower.tail=FALSE) = 0.8281

Approximating Pi

Next we'll move on to something a bit trickier, approximating Pi!

We'll start by refreshing on some basic facts. The area of a circle is $$A_ = \pi r^2$$ and if we draw a square containing that circle its area will be $$A_ = 4r^2$$ this is because each side is simply \(2r\) as can be seen in this image:

Basic properties of a circle

Now how do we get \(\pi\)? The ratio of the area of the circle to the area of the square is$$\frac{\pi r^2}$$ which we can reduce to simply $$\frac$$ Given this fact, if we can empiricaly determine the ratio of the area of the circle to the area of the square we can simply multiply this number by 4 and we'll get our approximation of \(\pi\).

To do this we can randomly sample \(x\) and \(y\) values from a unit square centered around 0. If \(x^2 + y^2 \leq r^2 \) then the point is in the circle (in this case \(r = 0.5\)). The ratio of points in the circle to total points sample multiplied by 4 should then approximate \(pi\).

runs <- 100000 #runif samples from a uniform distribution xs <- runif(runs,min=-0.5,max=0.5) ys <- runif(runs,min=-0.5,max=0.5) in.circle <- xs^2 + ys^2 <= 0.5^2 mc.pi <- (sum(in.circle)/runs)*4 plot(xs,ys,pch='.',col=ifelse(in.circle,"blue","grey") ,xlab='',ylab='',asp=1, main=paste("MC Approximation of Pi =",mc.pi))

Sampling 100,000 points inside and outside of a circle

The more runs we have the more accurately we can approximate \(\pi\).

Finding our own p-values

Let's suppose we're comparing two webpages to see which one converts our customers to "sign up" at a higher rate (This is commonly referred to as an A/B Test). For page A we have seen 20 convert and 100 not convert, for page B we have 38 converting and 110 not converting. We'll model this as two Beta distributions as we can see below:

Visualizing the possible overlap between two Beta distributions

It certainly looks like B is the winner, but we'd really like to know how likely this is. We could of course run a single tailed t-test, that would require that we assume that these are Normal distributions (which isn't a terrible approximation in this case). However we can also solve this via a Monte Carlo simulation! We're going to take 100,000 samples from A and 100,000 samples from B and see how often A ends up being larger than B.

runs <- 100000 a.samples <- rbeta(runs,20,100) b.samples <- rbeta(runs,38,110) mc.p.value <- sum(a.samples > b.samples)/runs

And we have mc.p.value = 0.0348

Awesome our results are "statistically significant"!

..but wait, there's more! We can also plot out a histogram for of the differences to see how big a difference there might be between our two tests!

hist(b.samples/a.samples)

By simulating samples between two distributions we can see the average improvement.

Now we can actually reason about how much of a risk we are taking if we go with B over A!

Games of chance

If we bring back the spinner from the post on Expectation we can play a new game!

The great spinner of probability!

In this game landing on 'yellow' you gain 1 point, 'red' you lose 1 point and 'blue' you gain 2 points. We can easily calculate the expectation: $$E(\text{spinner}) = 1/2 \cdot 1 + 1/4 \cdot -1 + 1/4 \cdot 2 = 0.75$$ This could have been calculated with a Monte Carlo simulation, but the hand calculation is really easy. Let's ask a trickier question "After 10 spins what is the probability that you'll have less then 0 points?" There are methods to analytically solve this type of problem, but by the time they are even explained we could have already written our simulation!

To solve this with a Monte Carlo simulation we're going to sample from our Spinner 10 times, and return 1 if we're below 0 other wise we'll return 0. We'll repeat this 100,000 times to see how often it happens!

runs <- 100000 #simulates on game of 10 spins, returns whether the sum of all the spins is < 1 play.game <- function(){ results <- sample(c(1,1,-1,2),10,replace=T) return(sum(results) < 0) } mc.prob <- sum(replicate(runs,play.game()))/runs

And now we have our estimate on the likelihood of having negative points after just 10 spins.

mc.prob = 0.01314

Predicting the Stock Market

Finally CountBayes.com has IPO'd! It trades under the ticker symbol BAYZ. On average it gains 1.001 times its opening price during the trading day, but that can vary by a standard deviation of 0.005 on any given day (this is its volatility). We can simulate a single sample path for BAYZ by taking the cumulative product from a Normal distribution with a mean of 1.001 and a sd of 0.005. Assuming BAYZ opens at $20/per share here is a sample path for 200 days of BAYZ trading.

days <- 200 changes <- rnorm(200,mean=1.001,sd=0.005) plot(cumprod(c(20,changes)),type='l',ylab="Price",xlab="day",main="BAYZ closing price (sample path)")

BAYZ Stock Ticker

But this is just one possible future! If you are thinking of investing in BAYZ you want to know what are the possible closing prices of the stock at the end of 200. To assess risk in this stock we need to know what are reasonable upper and lower bounds on the future price.

To solve this we'll just simulate 100,000 different possible paths the stock could take and then look at the distribution of closing prices.

runs <- 100000 #simulates future movements and returns the closing price on day 200 generate.path <- function(){ days <- 200 changes <- rnorm(200,mean=1.001,sd=0.005) sample.path <- cumprod(c(20,changes)) closing.price <- sample.path[days+1] #+1 because we add the opening price return(closing.price) } mc.closing <- replicate(runs,generate.path())

The median price of BAYZ at the end of 200 days is simply median(mc.closing) = 24.36

but we can also see the upper and lower 95th percentiles

quantile(mc.closing,0.95) = 27.35

quantile(mc.closing,0.05) = 21.69

NB - This is a toy model of stock market movements, even models that are generally considered poor models of stock prices at the very least would use a log-normal distribution. But those details deserve a post of their own! Real world quantitative finance makes heavy use of Monte Carlo simulations.

Just the beginning!

By now it should be clear that a few lines of R can create extremely good estimates to a whole host of problems in probability and statistics. There comes a point in problems involving probability where we are often left no other choice than to use a Monte Carlo simulation. This is just the beginning of the incredible things that can be done with some extraordinarily simple tools. It also turns out that Monte Carlo simulations are at the heart of many forms of Bayesian inference.

For more examples of using Monte Carlo Simulations check out these posts:

Build your own Rejection Sampler in R.

Using a MC simulation to solve a variant of the Coupon Collectors Puzzle.

As an alternative, Solve Markov Chains with Linear Algebra instead of Monte Carlo Methods

Learn more about Bayesian Statistics with my new book Bayesian Statistics the Fun Way!